Treating Hip Dysplasia in Young Adults

The hip is a "ball-and-socket" joint. In a normal hip, the ball at the upper end of the femur (thighbone) fits firmly into the socket, which is a curved portion of the pelvis called the acetabulum. In a young person with hip dysplasia, the hip joint has not developed normally—the acetabulum is too shallow to adequately support and cover the head of the femur. This abnormality can cause a painful hip and the early development of osteoarthritis, a condition in which the articular cartilage in the joint wears away and bone rubs against bone.

Adolescent hip dysplasia is usually the end result of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a condition that occurs at birth or in early childhood. Although infants are routinely screened for DDH, some cases remain undetected or are mild enough that they are left untreated. These patients may not show symptoms of hip dysplasia until reaching adolescence.

The magnitude and severity of hip dysplasia can vary from patient to patient. In mild cases, the head of the femur may simply be loose in the socket. In more severe cases, there may be complete instability in the joint and/or the femoral head may be completely dislocated out of the socket.

Treatment for adolescent hip dysplasia focuses on relieving pain while preserving the patient's natural hip joint for as long as possible. In many cases, this is achieved through surgery to restore the normal anatomy of the joint and delay or prevent the onset of painful osteoarthritis.

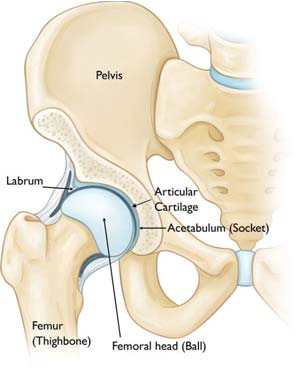

What is the anatomy of the hip?

The hip is one of the body's largest joints. It is a "ball-and-socket" joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is a part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

The bone surfaces of the ball and socket are covered with articular cartilage, a smooth, slippery substance that protects and cushions the bones and enables them to move easily.

The acetabulum is lined with fibrocartilage called the labrum. The labrum creates a tight seal to hold the femoral head in place.

What causes hip dysplasia?

Adolescent hip dysplasia usually results from developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) that is undiscovered or untreated during infancy or early childhood. DDH tends to run in families. It can be present in either hip and in any individual. It usually affects the left hip and occurs more often in:

- Girls

- First-born children

- Babies born in the breech position

What are the symptoms of hip dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia, itself, is not a painful condition. However, pain results when the altered forces in the hip cause degenerative changes to occur in the articular cartilage and the labrum. In most cases, this pain is:

- Located in the groin area, although it may sometimes be more toward the outside of the hip

- Occasional and mild initially, but may increase in frequency and intensity over time

- Worse with activity or near the end of the day

Some patients may also experience the feeling of locking, catching, or popping within the groin.

How is hip dysplasia diagnosed?

Physical Exam

During the physical examination, your provider will discuss your medical history and symptoms. They will move your hip in different directions to assess the range of motion and duplicate the pain or discomfort he or she is feeling.

Imaging

In most cases, adolescent hip dysplasia can be diagnosed with just a physical exam. Imaging tests may be used to rule out other causes for your pain and to help confirm the diagnosis.

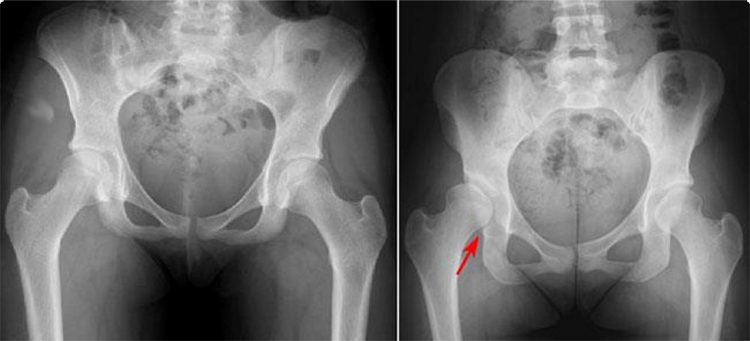

(Left) This x-ray shows two normal hips. (Right) This x-ray shows a dysplastic hip. The hip socket is shallow and there is only partial coverage of the femoral head.

- X-rays. Insert Hip Dysplasia Xray image. These provide images of dense structures such as bone, and will help your doctor assess the alignment of the acetabulum and femoral head. An x-ray can also show signs of arthritis.

- Computed tomography (CT) scans. More detailed than a plain x-ray, CT scans can help your doctor establish the degree of dysplasia.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These studies can create better images of the body's soft tissues. An MRI can help your doctor find damage to the labrum and articular cartilage.

How is hip dysplasia treated without surgery?

Treatment for adolescent hip dysplasia focuses on delaying or preventing the onset of osteoarthritis while preserving the natural hip joint for as long as possible.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend nonsurgical treatment if you have mild hip dysplasia and no damage to the labrum or articular cartilage. Nonsurgical treatment may also be tried initially for patients who have such extensive joint damage that the only surgical option would be a total hip replacement.

- Observation. If you have minimal symptoms and mild dysplasia, your doctor may recommend simply monitoring the condition to make sure it does not get worse. You will have follow-up visits every 6 to 12 months so that the doctor can check for any progression that may warrant treatment.

- Lifestyle modification. Your doctor may also recommend that you avoid the activities that cause the pain and discomfort. For someone who is overweight, losing weight will also help to reduce pressure on the hip joint.

- Physical therapy. Specific exercises can improve the range of motion in the hip and strengthen the muscles that support the joint. This can relieve some stress on the injured labrum or cartilage.

- Medications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and naproxen, can help relieve pain and reduce swelling in an arthritic joint. In addition, cortisone is an anti-inflammatory agent that can be injected directly into a joint. Although an injection of cortisone can provide pain relief and reduce inflammation, the effects are temporary.

What surgical treatments are available for hip dysplasia?

Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO)

Currently, the procedure most commonly used to treat adolescent hip dysplasia is a periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). "Periacetabular" means "around the acetabulum." In most cases, PAO takes from 2-3 hours to perform. During the surgery, the doctor makes four cuts in the pelvic bone around the hip joint to loosen the acetabulum. They then rotate the acetabulum, repositioning it into a more normal anatomic position over the femoral head. The doctor will use x-rays to direct the bony cuts and to ensure that the acetabulum is repositioned correctly. Once the bone is repositioned, the doctor inserts several small screws to hold it in place until it heals.

Arthroscopy

In conjunction with PAO, your doctor may use hip arthroscopy to repair a torn labrum. During arthroscopy, the doctor inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into the joint. The camera displays pictures on a television screen, and your doctor uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments. Arthroscopic procedures may include:

- Labral refixation. In this procedure, the doctor trims the torn and frayed tissue around the acetabular rim and reattaches the torn labrum to the bone of the rim.

- Debridement. In some cases, simply removing the torn or weakened labral tissue can provide pain relief.

What is recovery from surgery like?

In most cases, full weight-bearing will not be allowed on the operated leg for 6 weeks to 3 months while the bones heal in their new position. During this time, you will need to use crutches. About 6 weeks after surgery, you will have a follow-up visit with the doctor. X-rays will be taken so that the doctor can see how well the PAO has healed. During your visit, the doctor will determine when it is safe to put weight on the leg and when physical therapy can begin. The physical therapist will show you specific exercises to help maintain range of motion and restore strength and flexibility in the hip joint.

How successful is surgery for treating hip dysplasia?

PAO is usually successful in delaying the need for an artificial hip joint and relieving pain. Whether or not a total hip replacement will be needed in the future depends on a number of factors, including the degree of osteoarthritis that was present in the joint when the PAO was performed.