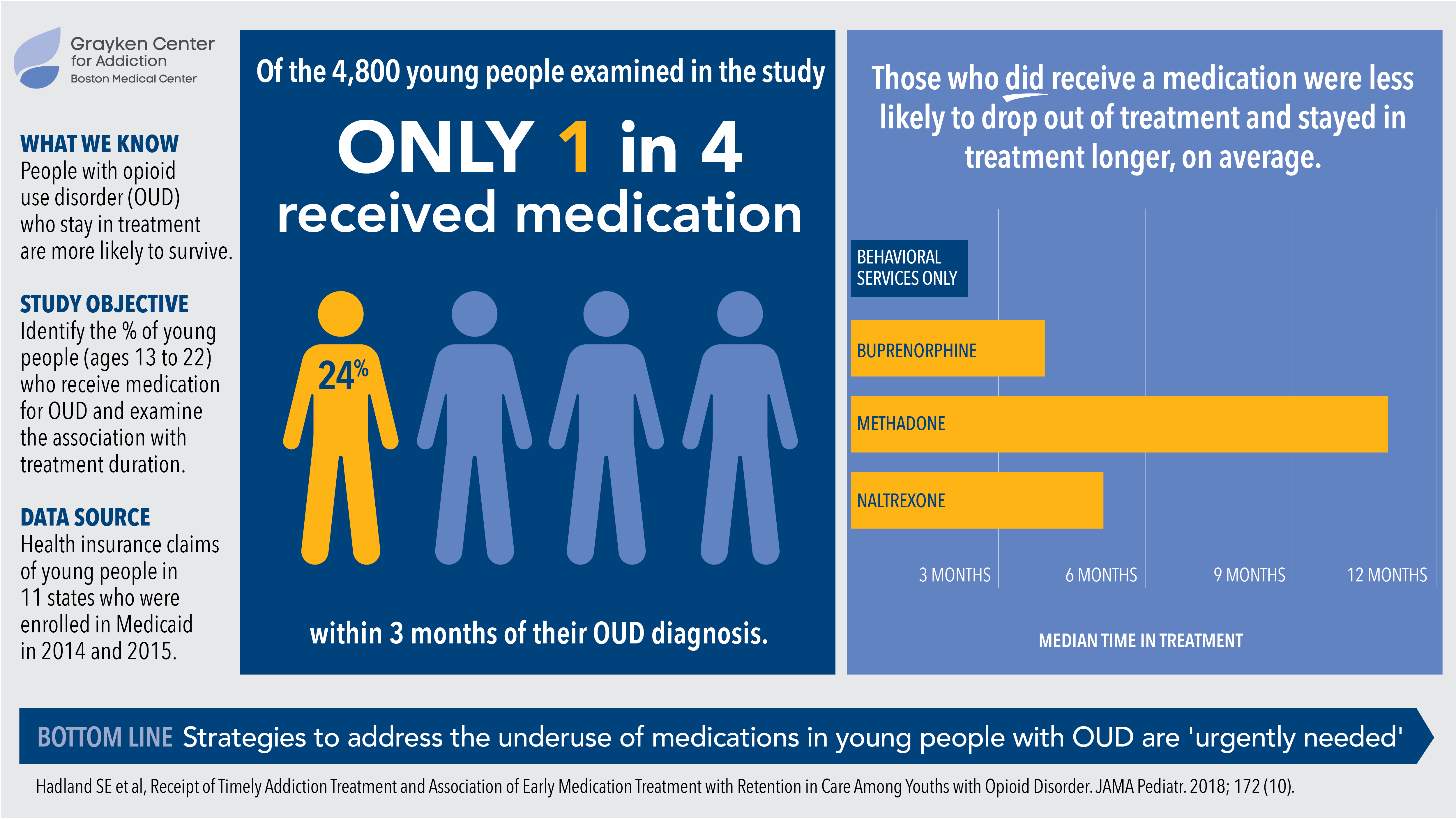

Boston – A majority of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with opioid use disorder are not receiving recommended medication to treat their disease, according to a new study led by Boston Medical Center’s Grayken Center for Addiction. The results show that only 24 percent of youths receive one of the FDA-approved medications – methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone – within three months of their diagnosis. That gap increases for those under the age of 18, with only one in 21 adolescents receiving a medication. Patients who receive medication are more likely to remain in treatment compared to those who only receive behavioral health services. Given the ever-increasing rate of opioid overdoses, the study underscores the need to address why evidence-based medications are underused to treat adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorder.

Published in JAMA Pediatrics, this study is the first to examine youths with opioid use disorder and how each medication impacts retention in treatment.

The retrospective cohort study examined health insurance claims for 2.4 million youths aged 13-22 years enrolled in Medicaid between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2015. During that time period, there were 4,837 youths diagnosed with opioid use disorder. Overall, 76 percent received treatment within three months of diagnosis. However, most of those youths, 69 percent, received only behavioral health services, such as individual and group sessions in outpatient and inpatient settings. For adolescents younger than 18, only 4.7 percent received medications within three months, and for young adults over the age of 18, 27 percent received medication within that timeframe.

“Our findings show that a serious gap exists in how we treat adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorder, and that this gap puts them at risk for discontinuing treatment early,” said Scott Hadland, MD, a pediatrician and researcher at the Grayken Center.

The median time that youths remained in care when they received buprenorphine was 123 days; for naltrexone, 150 days; and for methadone, 324 days. For behavioral health services alone, that number was only 67 days.

The recognition of addiction as a chronic disease where patients may relapse is an important aspect of treatment. Recent studies indicate that keeping patients engaged in treatment is critical to their recovery and protects against early death. Even if they do not abstain or reduce their substance use, being in treatment allows them to receive harm reduction services as well as treatment for other medical and psychiatric conditions. However, the authors note, there are too many barriers for youths to access medications to treat their opioid use disorder.

“There are far too few pediatric providers who prescribe medications for addiction, and stigma is still playing a role in deterring many patients and families from using these evidence-based medications,” said Hadland, also assistant professor of pediatrics at BU School of Medicine. Of all addiction treatment programs for youth across the country listed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, only 37 percent offer methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone, and of the remaining programs, a staggering 43 percent will deny admission to young people who are already on these medications.

“Recovery is a long journey that is not just about eliminating or reducing substance use, but also about keeping patients engaged in care,” added Hadland. “Providers, lawmakers and researchers must do more to improve treatment for adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorder.”

# # #

Media Contact:

mediarelations@bmc.org en

en

Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Español

Español Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt Kreyol ayisyen

Kreyol ayisyen