(Left) The proximal tibia is the upper portion of the bone, closest to the knee. (Right) Ligaments connect the femur to the tibia and fibula (kneecap not shown).

A fracture, or break, in the shinbone just below the knee is called a proximal tibia fracture. The proximal tibia is the upper portion of the bone where it widens to help form the knee joint.

In addition to the broken bone, soft tissues (skin, muscle, nerves, blood vessels, and ligaments) may be injured at the time of the fracture. Both the broken bone and any soft- tissue injuries must be treated together. In many cases, surgery is required to restore strength, motion, and stability to the leg, and reduce the risk for arthritis.

The knee is the largest weight-bearing joint of the body. Three bones meet to form the knee joint: the femur (thighbone), tibia (shinbone), and patella (kneecap). Ligaments and tendons act like strong ropes to hold the bones together. They also work as restraints — allowing some types of knee movements, and not others. In addition, the way the ends of the bones are shaped help to keep the knee properly aligned.

What are the different types of upper shinbone fractures?

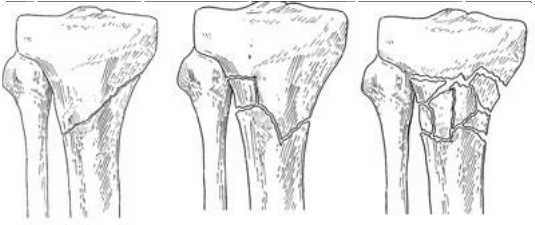

There are several types of upper shinbone fractures. The bone can break straight across (transverse fracture) or into many pieces (comminuted fracture)

Examples of different types of proximal tibia fractures.

Sometimes these fractures extend into the knee joint and separate the surface of the bone into a few (or many) parts. These types of fractures are called intra-articular or tibial plateau fractures.

The top surface of the tibia (the tibial plateau) is made of cancellous bone, which has a "honeycombed" appearance and is softer than the thicker bone lower in the tibia.

Fractures that involve the tibial plateau occur when a force drives the lower end of the thighbone (femur) into the soft bone of the tibial plateau, similar to a die punch. The impact often causes the cancellous bone to compress and remain sunken, as if it were a piece of Styrofoam that has been stepped on.

This damage to the surface of the bone may result in improper limb alignment, and over time may contribute to arthritis, instability, and loss of motion.

Proximal tibia fractures can be closed — meaning the skin is intact — or open. An open fracture is when a bone breaks in such a way that bone fragments stick out through the skin or a wound penetrates down to the broken bone. Open fractures often involve much more damage to the surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments. They have a higher risk for problems like infection, and take a longer time to heal.

What causes upper tibia fractures?

A fracture of the upper tibia can occur from stress (minor breaks from unusual excessive activity) or from already compromised bone (as in cancer or infection). Most, however, are the result of trauma (injury).

Young people experience these fractures often as a result of a high-energy injury, such as a fall from considerable height, sports-related trauma, and motor vehicle accidents.

Older persons with poorer quality bone often require only low-energy injury (fall from a standing position) to create these fractures.

What are symptoms of an upper tibia fracture?

Symptoms include:

- Pain that is worse when weight is placed on the affected leg

- Swelling around the knee and limited bending of the joint

- Deformity — The knee may look "out of place"

- Pale, cool foot — A pale appearance or cool feeling to the foot may suggest that the blood supply is in some way impaired.

- Numbness around the foot — Numbness, or "pins and needles," around the foot raises concern about nerve injury or excessive swelling within the leg.

If you have these symptoms after an injury, go to the nearest hospital emergency room for an evaluation.

How is an upper tibia fracture diagnosed?

Medical History and Physical Examination

Your provider will ask for details about how the injury happened. He or she will also talk to you about your symptoms and any other medical problems you may have, such as diabetes.

Your provider will examine the soft tissue surrounding the knee joint. He or she will check for bruising, swelling, and open wounds, and will assess the nerve and blood supply to your injured leg and foot.

Tests

X-rays. The most common way to evaluate a fracture is with x-rays, which provide clear images of bone. X-rays can show whether a bone is intact or broken. They can also show the type of fracture and where it is located within the tibia.

Computed tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan shows more detail about your fracture. It can provide your provider with valuable information about the severity of the fracture and help your provider decide if and how to fix the break.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. An MRI scan provides clear images of soft tissues, such as tendons and ligaments. Although it is not a routine test for tibia fractures, your provider may order an MRI scan to help determine whether there are additional injuries to the soft tissues surrounding your knee. In addition, if you have all the signs of a tibial plateau fracture, but x-rays are negative, your provider may order an MRI scan. When bone is injured there is often reaction in the bone marrow which can be detected on MRI and means that a fracture has occurred.

Other tests. Your provider may order other tests that do not involve the broken leg to make sure no other body parts are injured (head, chest, belly, pelvis, spine, arms, and other leg). Sometimes, other studies are done to check the blood supply to your leg.

How is a broken upper tibia treated?

A proximal tibia fracture can be treated nonsurgically or surgically. There are benefits and risks associated with both forms of treatment.

Whether to have surgery is a combined decision made by the patient, the family, and the provider. The preferred treatment is accordingly based on the type of injury and the general needs of the patient.

When planning treatment, your provider will consider several things, including your expectations, lifestyle, and medical condition.

In an active individual, restoring the joint through surgery is often appropriate because this will maximize the joint's stability and motion, and minimize the risk of arthritis.

In other individuals, however, surgery may be of limited benefit. Medical concerns or pre- existing limb problems might make it unlikely that the individual will benefit from surgery. In such cases, surgical treatment may only expose these individuals to its risks (anesthesia and infection, for example).

Emergency Treatment

Open fractures. If the skin is broken and there is an open wound, the underlying fracture may be exposed to bacteria that might cause infection. Early surgical treatment will cleanse the fracture surfaces and soft tissues to lessen the risk of infection.

External fixation. If the soft tissues (skin and muscle) around your fracture are badly damaged, or if it will take time before you can tolerate a longer surgery because of health reasons, your provider may apply a temporary external fixator. In this type of operation, metal pins or screws are placed into the middle of the femur (thighbone) and tibia (shinbone). The pins and screws are attached to a bar outside the skin. This device holds the bones in the proper position until you are ready for surgery.

Compartment syndrome. In a small number of injuries, soft-tissue swelling in the calf may be so severe that it threatens blood supply to the muscles and nerves in the leg and foot. This is called compartment syndrome and may require emergency surgery. During the procedure, called a fasciotomy, vertical incisions are made to release the skin and muscle coverings. These incisions are often left open and then stitched closed days or weeks later as the soft tissues recover and swelling resolves. In some cases, a skin graft is required to help cover the incision and promote healing.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment may include casting and bracing, in addition to restrictions on motion and weight bearing. Your provider will most likely schedule additional x-rays during your recovery to monitor whether the bones are healing well while in the cast. Knee motion and weight-bearing activities begin as the injury and method of treatment allow.

Surgical Treatment

There are a few different methods that a surgeon may use to obtain alignment of the broken bone fragments and keep them in place while they heal.

Internal fixation. During this type of procedure, the bone fragments are first repositioned (reduced) into their normal position. They are held together with special devices, such as an intramedullary rod or plates and screws.

In cases in which the upper one fourth of the tibia is broken, but the joint is not injured, a rod or plate may be used to stabilize the fracture. A rod is placed in the hollow medullary cavity in the center of the bone. A plate is placed on the outside surface of the bone.

Plates and screws are commonly used for fractures that enter the joint. If the fracture enters the joint and pushes the bone down, lifting the bone fragments may be required to restore joint function. Lifting these fragments, however, creates a hole in the cancellous bone of the region. This hole must be filled with material to keep the bone from collapsing. This material can be a bone graft from the patient or from a bone bank. Synthetic or naturally occurring products which stimulate bone healing can also be used.

External fixators. In some cases, the condition of the soft tissue is so poor that the use of a plate or rod might threaten it further. An external fixator (described under Emergency Care above) may be considered as final treatment. The external fixator is removed when the injury has healed.

What is the recovery process like after breaking the upper tibia?

Early Motion

Your provider will decide when it is best to begin moving your knee in order to prevent stiffness. This depends on how well the soft tissues (skin and muscle) are recovering and how secure the fracture is after having been fixed.

Early motion sometimes starts with passive exercise: a physical therapist will gently move your knee for you, or your knee may be placed in a continuous passive motion machine that cradles and moves your leg.

If your bone was fractured in many pieces or your bone is weak, it may take longer to heal, and it may be a longer time before your provider recommends motion activities.

Weight Bearing

To avoid problems, it is very important to follow your provider's instructions for putting weight on your injured leg.

Whether your fracture is treated with surgery or not, your provider will most likely discourage full weight bearing until some healing has occurred. This may require as much as 3 months or more of healing before full weight bearing can be done safely. During this time, you will need crutches or a walker to move around. You may also wear a knee brace for additional support.

Your provider will regularly schedule x-rays to see how well your fracture is healing. If treated with a brace or cast, these regular x-rays show your provider if the bone is changing position. Once your provider determines that your fracture is not at risk for changing position, you may start putting more weight on your leg. Even though you can put weight on your leg, you may still need crutches or a walker at times.

Rehabilitation

When you are allowed to put weight on your leg, it is very normal to feel weak, unsteady, and stiff. Even though this is expected, be sure to share your concerns with your provider and physical therapist. A rehabilitation plan will be designed to help your regain as much function as possible.

Your physical therapist is like a coach guiding you through your rehabilitation. Your commitment to physical therapy and making healthy choices can make a big difference in how well you recover. For example, if you are a smoker, your doctor or therapist may recommend that you quit. Some providers believe that smoking may prevent bone from healing. Your providers or therapist may be able to recommend professional services to help you quit smoking.

Departments and Programs Who Treat This Condition

Fracture Surgery

Orthopedic Surgery

Fracture Care

Physical and Occupational Therapy

es

es

English

English Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt Kreyol ayisyen

Kreyol ayisyen